What is GRASPS?

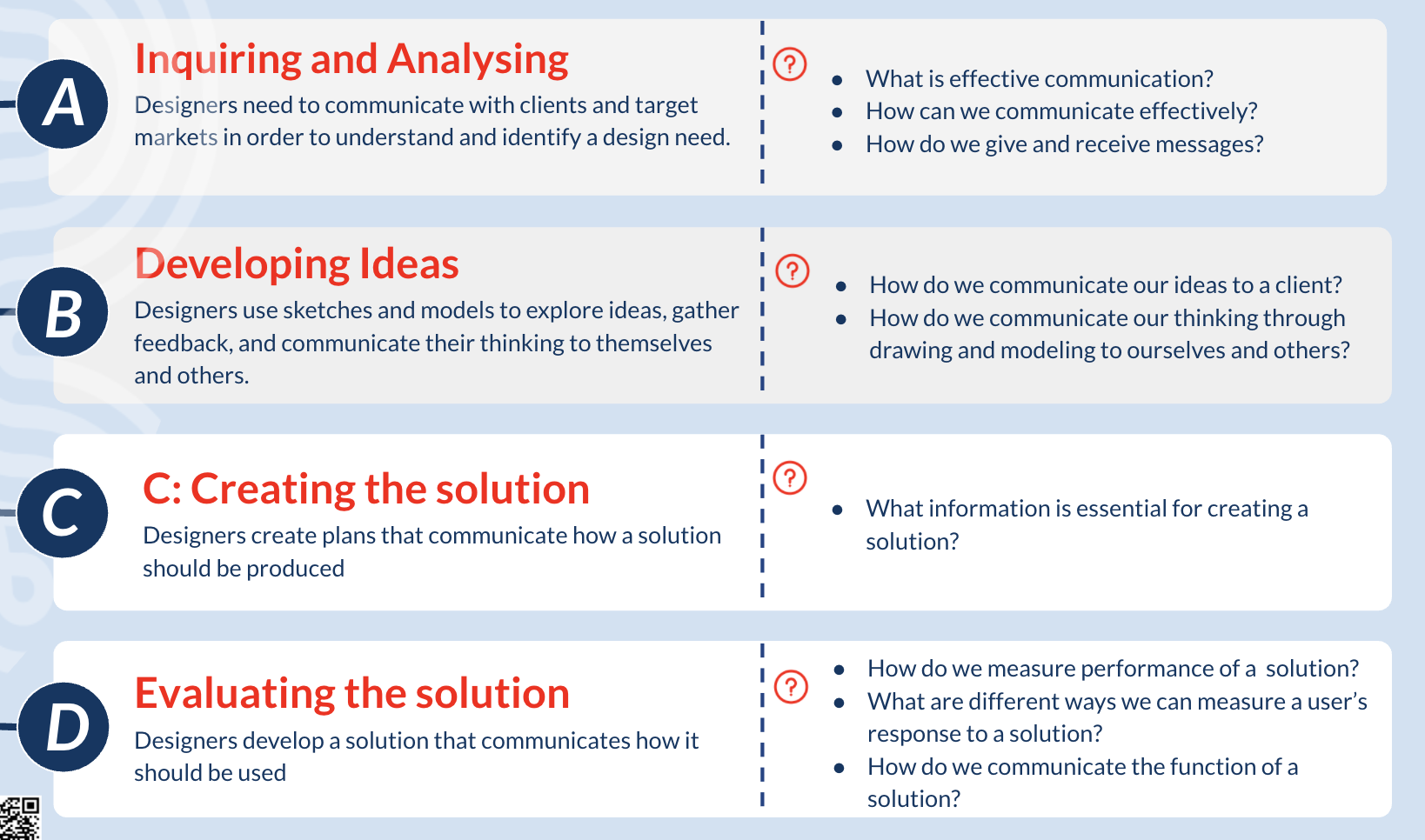

GRASPS is a model for demonstrating performance of understanding using authentic assessments. It is one of many performance of understanding models, but is ideally suited to the kind of project-based inquiries we do in design. GRASPS represent a framework for organizing, delivering, and assessing a project-based assessment. The assessment associated with the inquiry is structured around the following expectations and goals.

Goal: A definition of the problem or goal

Role: Define the role of the student

Audience: Identify the target audience

Situation: This is the context or scenario of the goal

Product: What is created and why it will be created

Standards: Rubrics or success criteria

Benefits of GRASPS

Over the years of organizing and implementing our units this way, we have noticed some benefits for students and teachers. Many of these observations are from the perspective of an MYP or DP classroom, but the underlying ideas would benefit any project-based learning experience.

From the teacher’s perspective, we have noticed:

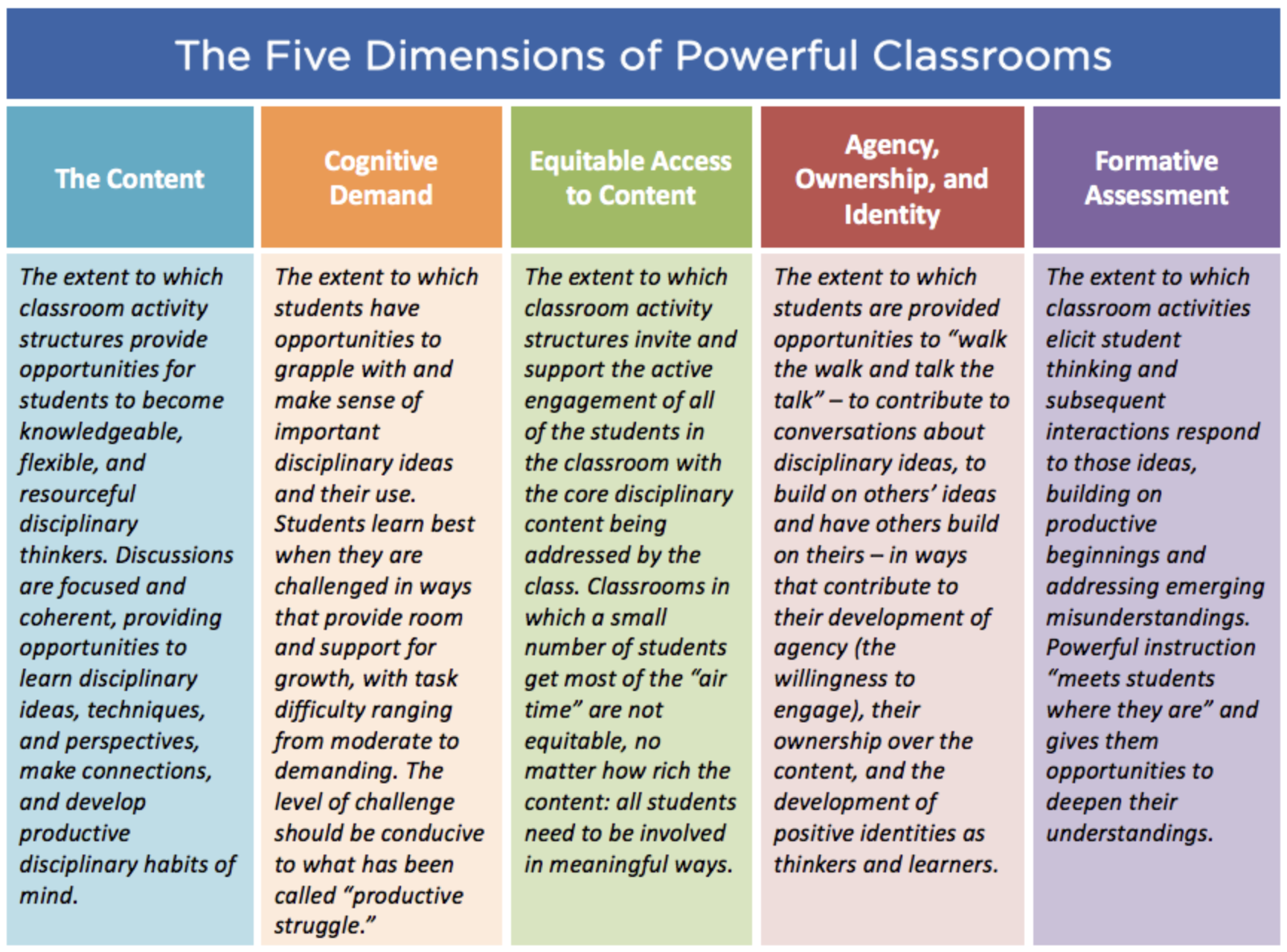

Develop authentic learning experiences: The overall GRASPS structure allows us to identify more authentic learning experiences that drive our units of inquiry.

Clearer presentation of the purpose and content of a project-based inquiry: Because of the way a GRASPS inquiry is framed, communication of the goals, content, and purpose of the inquiry is clearer. During planning it is easier for teachers to plan and develop more authentic units. This has become particularly important for collaboration between teachers, as most our units are planned to be taught by several people.

Clarify the roles, perspectives, and responsibilities of students: The GRASPS model clarifies these aspects of the inquiry. Teachers can choose resources, learning experiences, and content to support the students’ development in these areas. In particular, the Role has become an important part of how we frame units to students (see below)

Communicate the expectations of the inquiry: The structure allows for clear communication of the rubric, assessment expectations, as well as the approaches to learning that students need to utilize to be successful. This has been particularly important in recent times when some of our teaching and learning has shifted to remote

Guide the selection of learning experiences, content and skills necessary for success: Through planning a unit around the GRASPS framework, teachers can think critically and creatively about the type of learning experiences that are needed to support the inquiry. We have started to look more broadly at the skills that re needed, with a particular focus on the Approaches to Learning (ATLs).

New understandings about GRASPS

Since employing GRASPS to guide our unit development, we have come to some understandings about aspects of the model that helping us strengthen the delivery of our units.

Role

In the past, we often defined the role of the student in a very brief way - almost like a job title. You will be a a designer, engineer, marketer, etc. However we found that this often relied on student’s assumptions of what the role is. The role is very important as it defines the perspective from which the student approaches the task.

Now, we spend some time considering the role of the student in this inquiry, the skills they need, and how this role is closely connected to the Goal, Audience, and Product. For example, in a unit that defines the role as a design researcher, we spend time in class unpacking what this role entails, and how it connected to the goal, audience, and product. We discuss and highlight the skills, perspectives, and approaches that a person in this role might need to draw upon in order to be successful.

Some questions we ask in the planning stages to help us better identify and describe the role include:

What are some authentic roles that are related to the goal or discipline?

How will students understand the scope and expectations of the role?

What prior knowledge about the role will students have?

What skills and knowledge will students need to be successful in this role?

Is there a role model that students can refer to or meet in person?

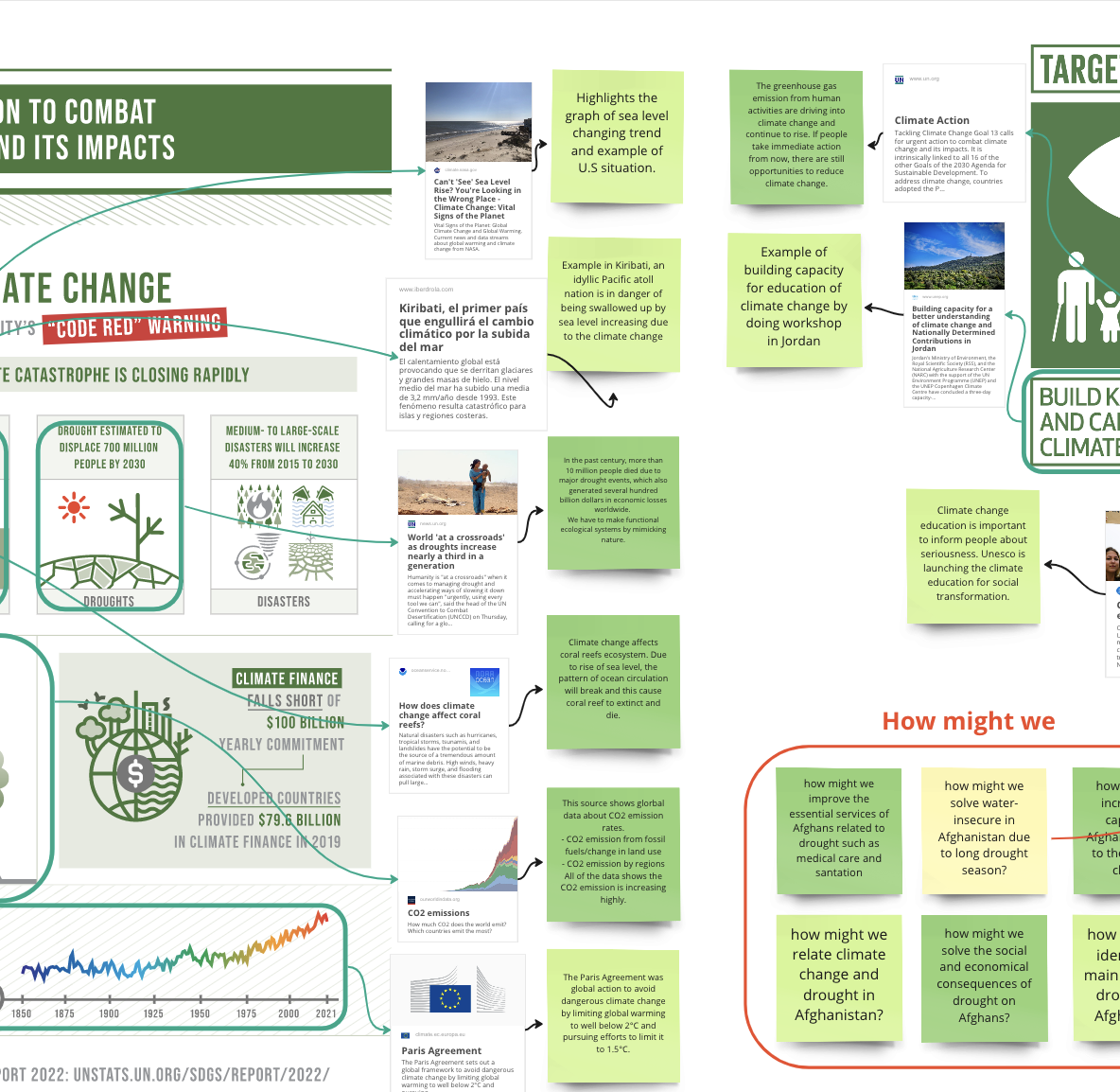

Audience

The audience provides much context to the inquiry. To this end, the audience helps teachers identify, organize, and prioritize the content and skills that students need in order to meet the needs of the audience. This goes beyond just satisfying the immediate needs of the audience, but also includes understanding the audience from a user-centered design perspective and empathizing with their needs in order to develop a more successful design solution. We’ve started to use User-Task-Environment analysis as part of the research approach. In Design, this approach also supports our research goals, and helps students think more broadly about the problem.

Some guiding questions we ask include:

What is the relationship between the audience and the role?

What are the defining characteristics of the audience, and how might these influence the skills and knowledge needed by students to be successful?

Developing stronger GRASPS assessments

To support teachers I’ve created a guide to developing a GRASPS assessment and incorporating into MYP and DP units of inquiry.