As design educators, we constantly strive to deliver a rigorous, authentic, and relevant curriculum that fosters critical thinking and creative problem-solving. In our experience at BHA, we've found that refining the MYP Design curriculum can significantly enhance student learning and engagement.

Read MoreUsing Miro to explore, collaborate, and communicate

Grade 10 inquiry into Biomimicry: What, How and Why.

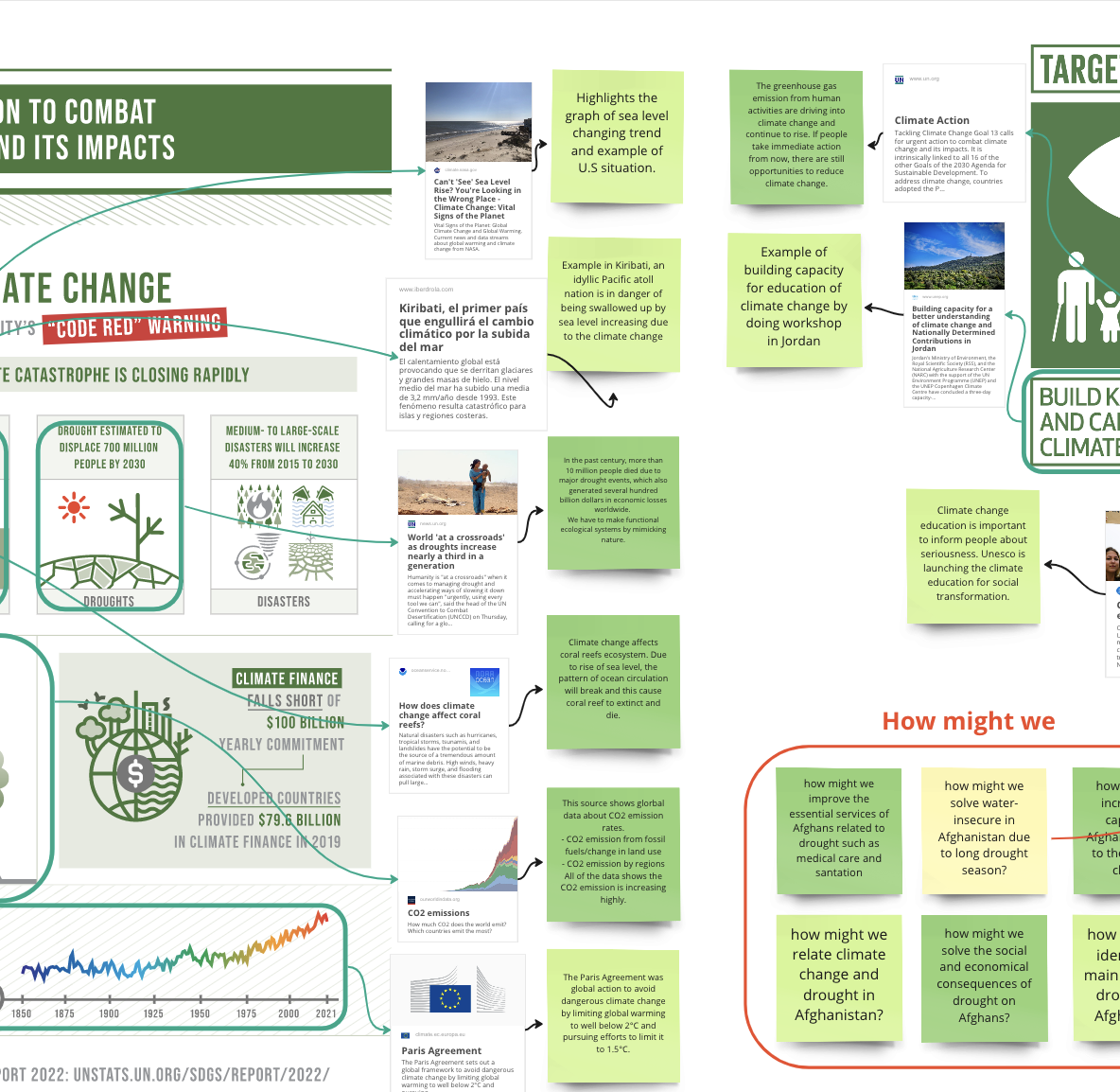

This year’s iteration presented us with the option of developing and iterating the unit. One of the key tools we used was Miro, an online collaboration tool, to structure, deliver, and guide the inquiry. We had about 90 students working on this task over three days. They worked in teams to learn about biomimicry, research into a problem, and develop a nature-inspired solution.

Read MoreThe 5 dimensions of an empathetic design-thinking classroom

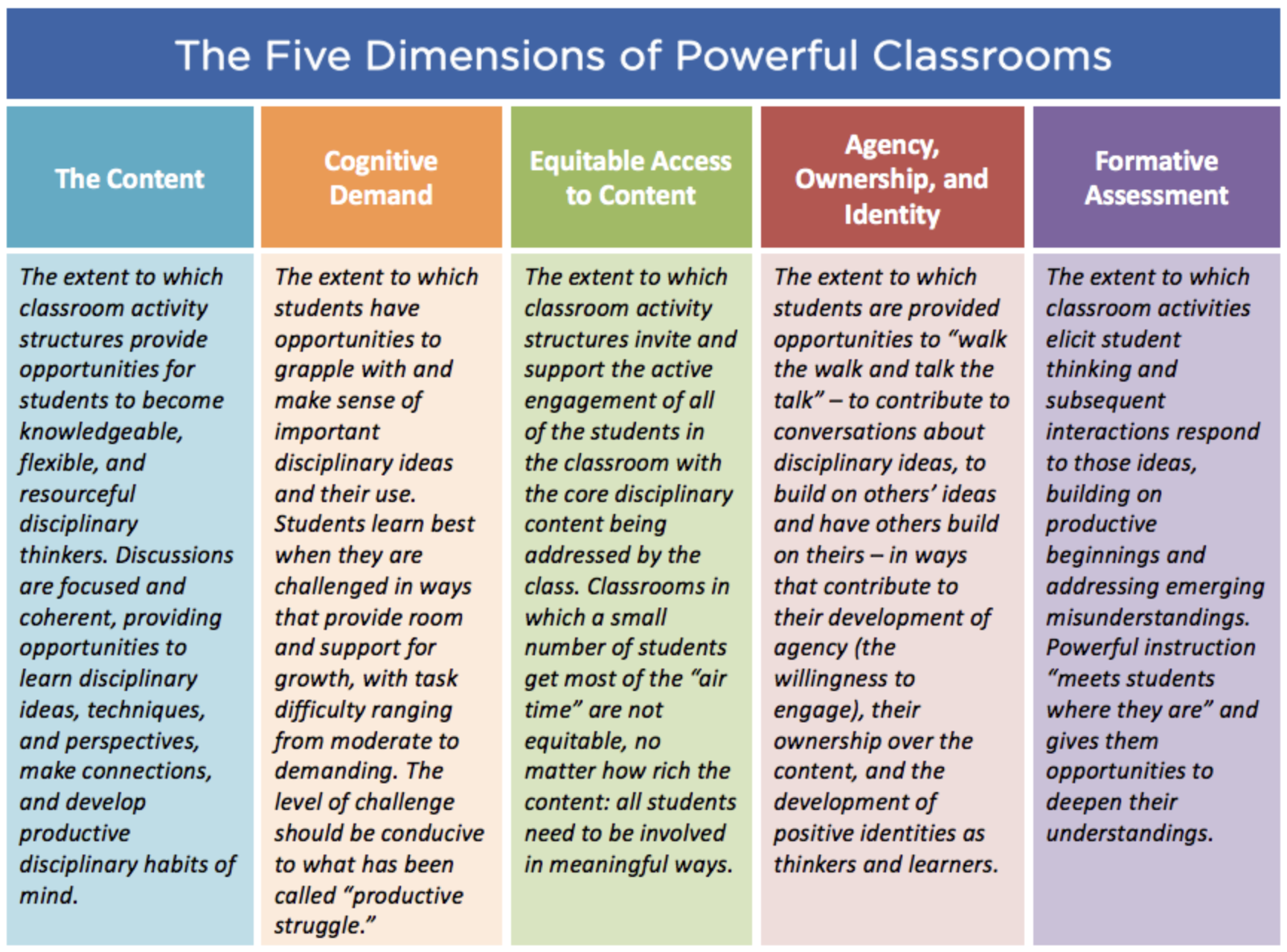

As part of my work in the HGSE Instructional Leadership course, we’ve been looking at the the characteristics of powerful learning environments. Design education provides so many interesting opportunities to explore, differentiate, and create learning environments that are authentic, rigorous, and engaging on so many levels. Our task was to articulate the elements of an empathetic classroom.

I’ve built my framework around the five perspectives of the TRU framework. This framework identifies five dimensions of empathetic classrooms:

I found that it aligned with much of my own perspective and philosophy - But needed more in order to make it applicable to my context as a design educator. I decided to connect to each perspective one of the Designerly Ways of Knowing, by design education researcher Nigel Cross. This is an influential work that has framed many of my approaches to design education. I found that as I started to think deeper about the TRU perspectives, that extending them actually aligned with Cross's ideas about design education.

In the MIRO board below, these as well as added some resources, if you're interested.

Assessment and Moderation in a Design Department

Opening up our gradebooks and sharing our assessment practices is an important way to reflect and learn about our teaching practice. In a program with multiple teachers for each grade level, being able to share our practice and get feedback on what is happening in our individual classrooms helps us as a team develop a more appropriate, rigorous, and consistent assessment standards.

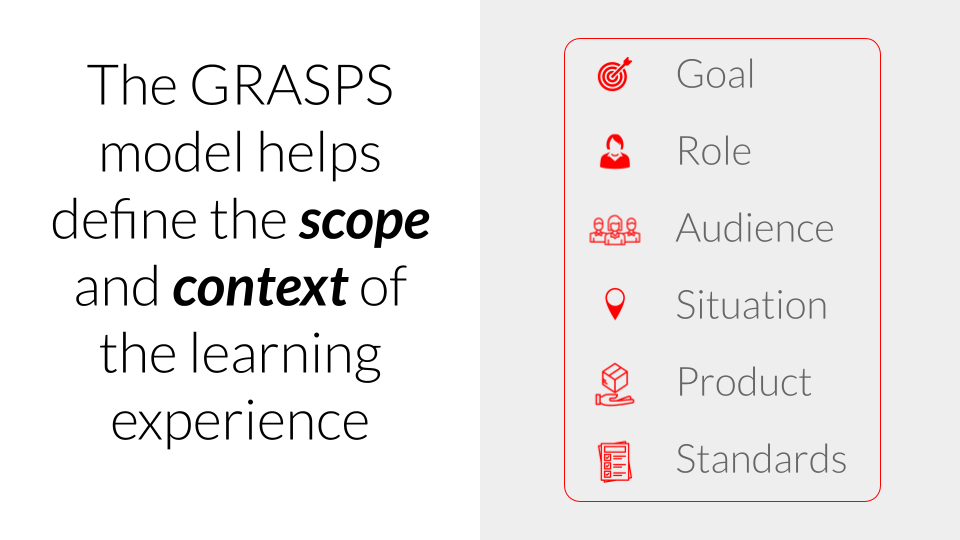

Read MoreRevisiting GRASPS: a model for project based learning

A while ago we started using GRASPS models to develop our units in MYP and DP design. I wrote about our initial work with this model a few years ago. Since then, we have used it to develop all our units in design and have noticed some meaningful results and benefits for both students and teachers.

What is GRASPS?

GRASPS is a model for demonstrating performance of understanding using authentic assessments. It is one of many performance of understanding models, but is ideally suited to the kind of project-based inquiries we do in design. GRASPS represent a framework for organizing, delivering, and assessing a project-based assessment. The assessment associated with the inquiry is structured around the following expectations and goals.

Goal: A definition of the problem or goal

Role: Define the role of the student

Audience: Identify the target audience

Situation: This is the context or scenario of the goal

Product: What is created and why it will be created

Standards: Rubrics or success criteria

Benefits of GRASPS

Over the years of organizing and implementing our units this way, we have noticed some benefits for students and teachers. Many of these observations are from the perspective of an MYP or DP classroom, but the underlying ideas would benefit any project-based learning experience.

From the teacher’s perspective, we have noticed:

Develop authentic learning experiences: The overall GRASPS structure allows us to identify more authentic learning experiences that drive our units of inquiry.

Clearer presentation of the purpose and content of a project-based inquiry: Because of the way a GRASPS inquiry is framed, communication of the goals, content, and purpose of the inquiry is clearer. During planning it is easier for teachers to plan and develop more authentic units. This has become particularly important for collaboration between teachers, as most our units are planned to be taught by several people.

Clarify the roles, perspectives, and responsibilities of students: The GRASPS model clarifies these aspects of the inquiry. Teachers can choose resources, learning experiences, and content to support the students’ development in these areas. In particular, the Role has become an important part of how we frame units to students (see below)

Communicate the expectations of the inquiry: The structure allows for clear communication of the rubric, assessment expectations, as well as the approaches to learning that students need to utilize to be successful. This has been particularly important in recent times when some of our teaching and learning has shifted to remote

Guide the selection of learning experiences, content and skills necessary for success: Through planning a unit around the GRASPS framework, teachers can think critically and creatively about the type of learning experiences that are needed to support the inquiry. We have started to look more broadly at the skills that re needed, with a particular focus on the Approaches to Learning (ATLs).

New understandings about GRASPS

Since employing GRASPS to guide our unit development, we have come to some understandings about aspects of the model that helping us strengthen the delivery of our units.

Role

In the past, we often defined the role of the student in a very brief way - almost like a job title. You will be a a designer, engineer, marketer, etc. However we found that this often relied on student’s assumptions of what the role is. The role is very important as it defines the perspective from which the student approaches the task.

Now, we spend some time considering the role of the student in this inquiry, the skills they need, and how this role is closely connected to the Goal, Audience, and Product. For example, in a unit that defines the role as a design researcher, we spend time in class unpacking what this role entails, and how it connected to the goal, audience, and product. We discuss and highlight the skills, perspectives, and approaches that a person in this role might need to draw upon in order to be successful.

Some questions we ask in the planning stages to help us better identify and describe the role include:

What are some authentic roles that are related to the goal or discipline?

How will students understand the scope and expectations of the role?

What prior knowledge about the role will students have?

What skills and knowledge will students need to be successful in this role?

Is there a role model that students can refer to or meet in person?

Audience

The audience provides much context to the inquiry. To this end, the audience helps teachers identify, organize, and prioritize the content and skills that students need in order to meet the needs of the audience. This goes beyond just satisfying the immediate needs of the audience, but also includes understanding the audience from a user-centered design perspective and empathizing with their needs in order to develop a more successful design solution. We’ve started to use User-Task-Environment analysis as part of the research approach. In Design, this approach also supports our research goals, and helps students think more broadly about the problem.

Some guiding questions we ask include:

What is the relationship between the audience and the role?

What are the defining characteristics of the audience, and how might these influence the skills and knowledge needed by students to be successful?

Developing stronger GRASPS assessments

To support teachers I’ve created a guide to developing a GRASPS assessment and incorporating into MYP and DP units of inquiry.

A UCD framework that builds empathy

Empathy is the driving force behind a successful design thinking project. Understanding the needs of the user is the key to successful design.

Read MoreReflecting on Designerly Ways of Knowing

The solution is not simply lying there among the data, like the dog among the spots in the well known perceptual puzzle; it has to be actively constructed by the designers own efforts.

Read MoreResearch for Designers: Using NoodleTools to scaffold inquiry

Research has taken on an important role in design, especially as we direct our students to undertake user centered design (UCD) approaches to their inquiry. Part of our approach in MYP Design incorporates tools such as NoodleTools to plan and organize research, and the user—task–environment framework for analyzing design opportunities. Together, these two tools help students organize their research, identify connections, and synthesize new understandings.

Below you can find a short workshop that I presented to faculty that outlines how we use NoodleTools to develop and support research skills (ATLs) in a design inquiry. You can see an example of that is incorporated as task-specific instruction here.

We are using Noodletools to scaffold the research process for students. After they have identified a source and created an MLA citation, we guide them in using the NoteCard feature to move their thinking from low-order (identifying) to high order (synthesis).

Continuum of Inquiry for Design and Science IDUs

Developing a Continuum of Inquiry: First steps

In Washington DC right now at the National Coalition of Girls Schools Global Forum II. My colleague, Kathy Binns, Head of Science, and I are presenting on our work integrating science and design in interdisciplinary projects. This has been a valuable opportunity for us to reflect on where our respective programs (Design and Science) are going, and how they overlap and support each other.

Our presentation shared what we have been doing and our thinking about future directions. As an IB school, we are focused on developing our students into inquirers and thinkers. Our interest lies in developing our students' skills to become collaborative and independent designers and thinkers.

Thinking of inquiry as a continuum, we have conceptualized it as above. Each grade level undertakes a large-scale IDU (Inter-Disciplinary Unit) during the course of the year. We envision these intensive experiences as opportunities to develop and apply skills and understandings, with each year building on the previous, towards a culmination in year 11.

- Grade 6: Collaborative experiences that develop these

- Grade 7: Presentation and Communication of learning

- Grade 8: Risk-taking to develop unique solutions

- Grade 9: Inquiry using data and iteration to solve challenging problems

- Grade 10: Applying research and analysis to synthesize new solutions to challenging problems

- Grade 11: Collaborative scientific inquiry to support the Group 4 project (a mandatory part of the DP curriculum)

The Grade 9 and Grade 10 projects dealt with sustainable energy production and biomimicry, respectively. This year, Grade 8 inquired into developing oil recover systems using robots. This was inspired by an oil spill of the cost of Jeju Island. Our grade 7 unit was performance art based, while the grade 6 explored digital media and story-telling.

This framework is the first step for us. It builds upon what we already have in our curriculums. Yet, we did not really know what had until we started to reflect on the connections. Based on some conversations with others at the conference, as well as watching some excellent presentations, we are inspired to iterate these IDUs further. Developing service opportunities and authentic audiences are our next steps, as well as strengthening the connections we already have are our two goals.